Meet the Mars Student Researcher Who Wants to Rewrite Fluid Dynamics

September 28, 2022

The Center for Planetary Systems Habitability provides research fellowships and travel grants that help students like Eric Hiatt make groundbreaking research about life on other worlds. Learn more at Opportunities. If you would like to support student research with a donation, please contact habitability@utexas.edu.

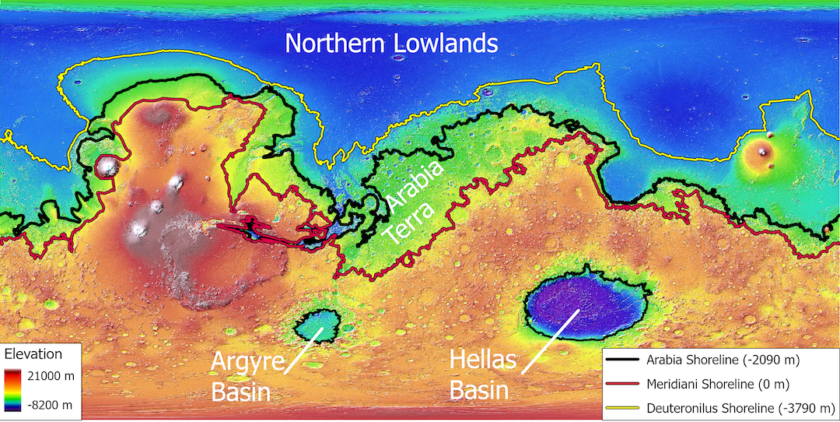

Mars was once a wet world, like Earth, but did water hang around long enough on its surface to sustain life?

That’s the question on the mind of Eric Hiatt, a graduate student at UT Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences, who’s supported by UT’s Center for Planetary Systems Habitability to study the history of water on Mars.

Hiatt’s research focuses on a period in Mars’ history during the Late Heavy Bombardment when asteroids slammed into the Red Planet, one after the other, leaving behind water-filled craters with bubbling hydrothermal systems.

“The thought is that as you dig out huge holes and the water flows between them, you can aggregate time in these environments,” he said. “To put it another way, can the water bounce between the impact crater hydrothermal systems and simulate a mid-ocean spreading center, like the ones where life is thought to have evolved on Earth?”

To find out whether life-supporting water could have hopped between hydrothermal systems, Hiatt dug into the mathematics of how groundwater seeps from one crater to another. His research raised fundamental problems in fluid dynamics that he hoped to answer through a combination of numerical models and laboratory water tank experiments.

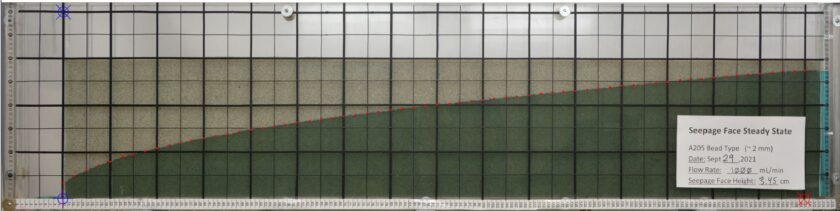

However, because no one had ever done experiments like that, getting the right equipment together wasn’t easy. Hiatt used what he could scrape together such as borrowed fish tank pumps, but the results, although promising, weren’t precise enough.

So, Hiatt applied for a student research grant with the UT Center for Planetary Systems Habitability and got funding for precision equipment, materials to simulate Mars soil, and a 3D printer to build whatever was missing. He also won a second grant that helped him free up time to build, test and perfect the equipment.

The result is a one-of-a-kind, two-dimensional emulator of how water flows between ocean pools on the surface of Mars. Although it’s still early days, the apparatus has already revealed some interesting patterns in the way water drains between craters, which current fluid dynamics models have no answer for. At least not yet.

According to Hiatt, the Center’s grants had been pivotal to his research and his career. Without them, he’d have been unable to test his numeric models.

“Grants like this are invaluable,” Hiatt said. “I just would not have this data without the generosity of the people who facilitate it. It’s creation of science and data that I think is going to be applicable across many fields, from tsunami models to contaminant transport in freshwater wells.”

Hiatt’s message for students thinking about research funding is ‘don’t hold back’.

“No idea is too big or too small,” he said. “Even if you’re not sure whether your idea is good enough go ahead and apply, see what they think of it. You’d be surprised what good ideas can come out of it.”

Student research grants at the UT Center for Planetary Systems Habitability give students access to resources they need to pursue frontier research in planetary habitability, from lab equipment to presenting their findings at major science conferences.